Daphne Wright – Emotional Archaeology

Arnolfini Bristol December 2016

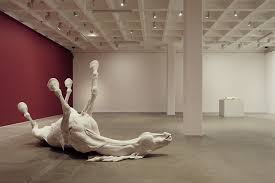

As you walk into the Gallery’s first room you are stumped by the majestic white stallion splayed on the floor (Figure 1). Fallen from its commanding stature with all its undercarriage on display, you start to explore what you think is there. This isn’t a horse rolling in play. You see the incision, the splitting and draping of the cut skin, the death of this beautiful creature. Sharing this gallery space are other animals, ghostlike in colour, hung up, laid out on plinths and as with the monkey, adorned with the most exquisite silk thread. They are casts that solidify what was there – whispers of slaughterhouses, laboratories and the tables of royals.

This first encounter evokes feelings of traditional sculpture steeped in historical and classical reference. The exhibition guide explains how ‘Swan’ refers to the Greek myth ‘Leda and the Swan’ and the material used which is marble dust and resin.

In Gallery 2 you walk into a room that feels a little disjointed. The guide describes this as an exploration of the subject of children and childhood from both child and adult’s perspective. To the left are Clay Heads, a collection of childlike heads, with gouges and incisions for eyes and mouths. They are like a realisation of children’s drawings. They feel disjointed with reference to the other works in the room but perhaps that is the intention. The gallery space is dominated by Kitchen Table (figure 2) which is central to the room. At a full size kitchen table adorned with tablecloth sits a small boy cross legged. His eyes are closed, his arms resting on his legs. He has no hair and just his underpants on. His chair sits empty. At the head of the table is another boy sat on a chair. His head rests on his left hand as he slouches onto his elbow at the table. This domestic setting is uncanny. Both boys are frozen in time, glimpses of a bored moment in an ordinary room. Yet, they appear slightly meditative, it is as if the artists’ process of meticulously casting their real bodies is what we witness. The curator, Jo Lanyon, describes the scene as the ‘familiar teatime routine’ (Lanyon: 2016:56). For me, the scene is far from familiar, it is more reminiscent of a futuristic scene devoid of emotion. As she approaches the children, Lanyon describes how the nearer she gets the further away the boys get, ‘there is shadow, echo and distance where there should be breath, smell and noise’ (Lanyon: 2016:56)

The scene is eerie, they remind me of the dead animals in the first gallery, yet this a moment of time in a domestic setting of Wrights’ children. There is no sentiment to this scene. This scene, in some ways, is no different to Still Life Plant (Figure 3) that sit on various walls. They are devoid of life and act like monuments of small moments. In an interview with Shirley MacWilliam, Wright talks Still Life Plant as being like memory. She retells a story of a friend whose son goes off to college leaving a houseplant in his room as a leftover of his life there, ‘they mark time, some strange kind of time.’ (WRIGHT in conversation with MacWilliam: 2016: 80. Edited by LANYON)

I wouldn’t describe this room as an exploration of children and childhood but more a collection of memories and moments that have become disturbed through realisation. It’s interesting that in conversation with Brian McAvera, Wright talks of suburban houses containing plaster casts of babies and children that are intended to become objects of a time or person in the past. She explains that in this process, ‘something is lost. By the time you cast an ear, the rest of the body has grown and so on and so forth. It’s the expression of the loss of a child: they go on to be adults’ (WRIGHT: in conversation with McAvera: 2016: 18. Edited by LANYON)

In contrast to this silent piece are monitors with looped films of two young boys with their faces painted, one with a beard and the other with a tiger (Figure 4). They are the questioner, and the viewer stands to be questioned. They are beautifully touching and intimate. We are caught engaging in play, question and guilt. One boy asks if we will remember him in a day, a week a month. The only answers are in the viewer’s head. ‘Knock Knock’ the boy says and we hear ourselves say, ‘who’s there? ‘. He replies to the silence, ‘You have forgotten me already’. As you turn from the video you pass the kitchen table again with ghosts of the boys you have forgotten.

Where Do Broken Hearts Go (Figure 5) is an installation of towering cacti like sculptures shining with silver foil. You feel as if you have stepped into a western film set with country and western songs playing. This room is surreal in comparison to other rooms. It certainly feels like something borrowed and alien; like a set on an old sci-fi film which is how McAvera also finds it. You hear an Irish woman talking of love and death. On the far wall is a collection of black and white images of nuns, children and one of a body laid out in a coffin. The room is quite eclectic and makes you think that you are in a disjointed dream with objects that exist yet the scale, material and sound are uncanny.

Domestic Shrubbery calls you in (Figure 6). You hear the faint ‘cuckoo’ from the gallery next door. The gentle maternal voice entices your childlike curiosity. The room closes in on you like a nest, surrounded by a walled trellis of 3d plaster floral wallpaper you see the small plaster hearts hanging amongst them. You want to reach out and touch these delicate walls, yet the voice gives you the feeling you are being watched and a slight feeling of claustrophobia creeps in the longer you stay. Lanyon talks of the cuckoo being a species that is already deemed an outsider as they lay their eggs in the nests of other birds. This aspect adds to the disturbance that occurs. Unsure whether you are meant to be inside or out, what first appears to be a gentle voice grows to a sinister one. If we consider the bird and the nest, then this piece goes further to dislodge our comfort. Bachelard talks of how we seek to find ‘nests’ within our own homes. Like creatures the nest gives complete refuge, positive metaphors of warmth, liveliness and the rhythm of life. Like it is to return home, this installation evokes the return to the nest yet there is no comfort here.

Lanyon describes Wright as an artist whose work is personal and political by exploring domestic and intimate issues. In her conversation with McAvera, Wright mentions being an ‘outsider’ and of ‘belonging and not belonging’ (WRIGHT: in conversation with McAvera: 2016: 23. Edited by LANYON). She talks of her interest of how a postcard can become more compelling than the original place. Perhaps this is what she comments on in her casting of objects and people and the pieces within this site of emotional archaeology.

Word count: 1208

Images