I want to explore through play with materials and space. To create environments and spaces. I want my process to rely on muscle memory, stored memories, attachment to compositions and patterns. To create with unconscious determination.

Considering the term ‘Mediascape’, I chose Yayoi Kusama as she is difficult to define by category or classification. She has shared affiliations to other art practices and artists. It is her installation work that interests me most. Resonating with elements of my studio practice I also chose her as I have experienced her work at The Tate (2012) and The Victoria Miro Gallery (2016). For the purpose of this essay I shall concern my thinking in terms of Installation Art.

When exploring Installation Art as a practice I wanted to also consider Bachelards’ Intimate Immensities from The Poetics of Space and ‘play’ as a process.

Using Kusama as an anchor in the Mediascape, I shall examine how her art practice has weaved throughout artistic traditions and practices to new and revolutionary practices. I will endeavour to trace the journey of Kusama’s practices in context to the landscape of developments of social consciousness and the art world. Touching briefly on celebrity culture, and how this has impacted on Kusama’s art practice, popularity and how she has manipulated this to her own advantage.

Kusama was born into a conservative, wealthy, traditional Japanese family with no support for her creative ambition. Through hard work and determination Kusama set her sights on travelling to New York in the late 1950’s to establish herself as ‘artist’. Kusama networked effectively with many artists in America becoming by the 1960’s well known in the Avant Garde world for her happenings and exhibits. Her performative happenings during the sixties ran in parallel with a revolutionary and radical decade in America. The civil rights movement created a more radical shift for all civil rights such as black power, feminism, sexual orientation and Anti-Vietnam protests. Her radical naked performances, staged orgies and nudist protests were linked to the move towards free love. Increasing her notoriety amongst the art world and the public. She impressed the art world with her Infinity Net paintings, her Accumulation Sculptures and her Installations. Much of Kusama’s work was overshadowed by male artists such as Claes Oldenburg, Bruce Nauman, Andy Warhol and Lucas Samaras whose works bear similarities to some of Kusama’s.

Kusama shared affiliations with other art movements and categories. These include Photography, Printmaking, Drawing, Surrealism, Pop Art, Abstraction, Installation and Painting. What is interesting about Kusama is that she never really stayed long enough to be attached, absorbed or labelled within a particular movement or category. Her practice crosses boundaries and transcends spaces yet doesn’t restrict her. She describes herself, seemingly proud, as a “heretic” of the art world. (Krasnow:1999)

By the 1970’s with the change in the cultural and political climate, interest in Kusama began to fade, criticisms of over exposure crept into the press and public eye. Kusama retreated with ill health and bouts of depression back to Japan. The shift in her work changed but her constant activity remained.

Today, Kusama’s work is exhibited worldwide. As Sullivan draws attention to how Kusamas’ work is mainly viewed in terms of “biography, feminism and psychoanalysis,” he examines how Kusamas’ work, “and its place within broader vanguard art practice of the period (is) being overlooked.” (Sullivan:2015: 406)

However, Artspace 2015, lists Kusama’s, Peepshow 1966 as one of “seven influential installation artworks you should know”. It includes other works by Mike Kelley, Robert Smithson, Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Kara Walker and Martin Kippenberger. It heralds Installation Art as, “proven to be one of the most vital artistic innovations of the past century.” It defines artists who do fit into this category by their acceptance that, “anything goes feeling” and that this art practice is not bogged down with any, “historical baggage.” What installation artists have in common is that they are all searching for a new, “aesthetic experience.” (Editors: 2015)

In a conversation with Storr, Kabakov has interesting observations about installation art and its’ relationship with painting. His analogy of painting is that of a “senile grandmother living in a family.” (Harrison & and Wood: 2002: 1175-1180) He explains that historically through education and experience we all know how to look at a painting, even the uneducated are not surprised or shocked by anything. His analogy of installation art is that of a “little girl who has just been born; she is still an infant, and no one knows what she will grow into.” (Harrison & and Wood: 2002) But, what she does have in her family is the senile grandmother with all her history and baggage. Kabakov emphasises that the problems arise for the viewer with installation art as they don’t quite know how to read it. I do agree with these analogies, yet, with Kusama, her use of familiar and childlike repetitive motifs and the immense intimate spaces that she creates, make it easier to experience without the need for history or knowledge. If painting is the window out or into, installation is the audience stepping through the window into an unknown territory.

I have chosen four installations to clarify some points within the essay.

It was the 1966 Venice Biennale which saw Kusama’s ground breaking work. Although not formally invited to exhibit, Kusama took up residency outside with her Narcissus Garden (Figure 1). Kusama placed herself as part of this piece, interacting and purposefully being documented being part of the work. Her manipulation of photography and self-promotion has been well documented and as did her motifs, became, “an essential, complex material element of the work – a means to promote herself.” (Sullivan: 2015:407) The mirrored balls reflected the image of those who held them. With 1,500 mirrored balls underneath a sign that read ‘Your Narcissism for Sale’, this piece was also political, commenting on the commercial nature of the art world. She interacted with passersby, ensuring she was photographed playing with the mirrored balls by throwing them into the air whilst dressed in her kimono. The piece continues to be exhibited and I saw it at Victoria Miro this year. Without the artist present and the context of the exhibit it became more a water feature (Figure 3). Causing some controversy at the time, Sullivan points out that as well as Kusama, there were other works by artists such as John Cage, Nam June Paik and Ay-O who by use of their media and participatory elements created a questioning of categories and definitions of fine art. (Sullivan: 2015)

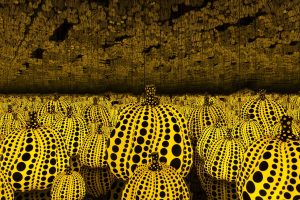

Reading Intimate Immensities resonated with Kusama’s’ mirrored installations. The artworks that reaffirm this link are, Chandelier of Grief (2016) (Figure 4), All the eternal love I have for Pumpkins (2016) (Figure 1) and Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Room 1965 (Figure 5). My experience of these installations are just as I experience in Bachelards’ writing.

Kusama’s installations are accumulations of repetitive lights, dots or pumpkins, she accumulates these individual marks that create larger, immense spaces. The viewer is part of the installation. Momentarily we are invited to daydream, transported to places that are endless, like the forest that Bachelard describes, there are no boundaries yet we feel contained. We bring our own history to what we experience and are participatory, yet still. Her mirrored installations enable us to be, “contemplating grandeur, this contemplation produces an attitude that is so special, an inner state that is so unlike any other that the daydream transports the dreamer outside the immediate world to a world that bears the mark of infinity.” (Bachelard: 1992: 183-210)

These intimate immense spaces exist momentarily but forever. If the gallery is busy our time is limited, yet, we sense the heaviness – the feeling of the familiar, the immensity, our sense we have journeyed, are now present and will always be afterwards. We leave with new memories and feelings. We are put at ease by the familiar and repetition of marks, revelling in understanding the grandeur attached to the pumpkin or the dot – we see ourselves in this immense space and we belong, not claustrophobic but still, calm, meditative, in awe. There may be feelings of the uncanny like a daydream, but there are no intimidating images or objects. Objects, such as the soft sculptures in Phalli’s Field, are emasculated, soft and covered in childlike spots, so rather than be sexual, they evoke a childlike, imaginary atmosphere. Phalli’s Field is made more interesting by handmade sculptures and are far less technically sophisticated than later work, such as Chandelier of Grief. We are put at ease by the handmade familiar motif of the pumpkin in All the love... We feel invited, can engage and be playful due to the imperfect, familiar object. We don’t feel excluded rather we are invited into a personal intimate space which is infinite and immense. There are no boundaries, beginning or end for just that moment. The door opens and our daydream is over.

Considering Kusama’s process I would like to look further into the childlike, playful elements of her work and processes. Kusama’s work is seen by some solely on an autobiographical level. With this in mind we can observe the polka dot and the pumpkin as images that stem from Kusama’s childhood. The motif of the pumpkin is likened by some to self-portraiture. These are the pumpkins that surrounded her family in the landscape and continue to occupy a significant personal place in her world. Kusama explains that, “Pumpkins have been a great comfort to me since my childhood; they speak to me of the joy of living” (Aouf: 2016). She has likened her repetitive dots or circles to the sun, the moon and infinity; using these to obliterate spaces, people or canvas. Much of her paintings, sculptures and installations consist of repetitive shapes and symbols. Whilst meditative and therapeutic they represent psychoanalytical theories on play and a ‘sense of being’ according to Winnicott whose work was published after the 1940’s. Winnicott explores a ‘sense of being’ can be lost in childhood. He believed that play was crucial for “authentic selfhood” and “only in playing are people their real selves” (Winnicott: 2009). We may see Kusama’s process as therapeutic or meditative or maybe it is her striving for her own ‘sense of being’. It is also worth considering Winnicott’s theories on ‘transitional objects’ when experiencing Kusama’s’ work. The word, ‘transition’ in this context means the intermediate developmental phase in between the external reality and the psychic. It is in the transitional space that Winnicott describes the ‘transitional object’. In her Accumulation works and Phalli’s Field she was photographed pressed against, laying down in and enveloped in these soft sculptures like a child amongst a flock of teddies. It is as if these were the transitional objects for the artist and the viewer. Perhaps as her work became more sophisticated she managed to empower the viewer to take charge of this transition by means of the familiar motif. These become the transitional objects that allow us to take familiar steps into her world.

There are many artists who strive for ‘authentic selfhood’ in the context of their work, which they demonstrate through their playful processes. Eduardo Paoulozzi, Philip Guston, Bruce Nauman, Eva Hesse and Richard Serra. These artists and theories are reaffirmed in how educational theorists believe that children learn best through play.

Kusama has been engineered as a public figure to who we can demonstrate huge admiration and empathy. Morris describes Kusama as a ‘globally branded artist…’, ‘celebrity artist of our era’ (Tateshots: 2012). Her work can be seen in levels of high and low art. What interests me is that her ‘celebrity status’ has created huge popular interest in her art, the work in 2016 is viewed by people who wouldn’t normally be interested in contemporary art. Partly this is due to its simplistic, beautiful aesthetic qualities but also how the public see her as a character; a quirky, eccentric mad oriental lady – like Kabakov’s senile grandmother. Much emphasis is placed upon her psychological state and her living arrangements, this appeals to the public. She becomes victim and they don’t feel intimidated; they are not excluded. This autobiographical aspect has raised criticism. Kavanagh (Artists Insight) explains his criticism thus, ‘we must feel that the artist has his or her finger on mankind’s pulse, not just their own. The being of the soul and of the inner workings of the personal unconscious will seem merely solipsistic if that principle is not observed.’ I agree the autobiographical shadows Kusama’s work, yet this feels as though it has been engineered by the curators and press. It deflects from the multi-talented, conceptual and ground breaking qualities in Kusama’s practice.

It is not only the context within the art world or movements in political, musical, philosophical thinking, education, cultural identities, gender and technology, but how an individual dot in an immense landscape that we cohabit, perceives and how we perceive them. It is increasingly harder to define art although there are still art practices or movements that can be categorised or labelled. Yet there are some artists who cross pollinate across art forms and integrate, experiment and change the landscape of art.

Images

Figure 1: Kusama. 2016. All the Eternal Love I have for the Pumpkins

Figure 2: Kusama. 1966. Narcissus Garden

Figure 3: Kusama. 2016. Narcissus Garden

Figure 4: Kusama. 2016. Chandelier of Grief

Figure 5: Kusama. 1965. Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field

Full List of Figures

Figure 1: KUSAMA, Yayoi. 2016. All the Eternal Love I have for the Pumpkins. Dezeen [online] Available at: https://static.dezeen.com/uploads/2016/06/all-the-eternal-love-i-have-for-pumpkins-yayoi-kusama-victoria-miro-exhibition-installation-art_dezeen_1568_3.jpg [accessed 30/10/2016]

Figure 2: KUSAMA, Yayoi. 1966. Narcissus Garden. History of Photography [online] Available at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03087298.2015.1093775?src=recsys [accessed 30/10/2016}

Figure 3: KUSAMA, Yayoi. 2016. Narcissus Garden. Artnet [online] Available at http://www.artnet.com/WebServices/images/ll1039645llgKUfDrCWBHBAD/yayoi-kusama-narcissus-garden.jpg [accessed 01/11/2016]

Figure 4: KUSAMA, Yayoi. 2016. Chandelier of Grief. Dezeen [online] Available at: https://static.dezeen.com/uploads/2016/06/chandelier-of-grief-yayoi-kusama-victoria-miro-exhibition-installation-art_dezeen_1568_5.jpg [Accessed: 30/10/16]

Figure 5: KUSAMA, Yayoi. 1965. Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field. Phaidon [online] Available at: http://www.phaidon.com/resource/kusama021.jpg [Accessed: 30/10/16]

List of References

Bibliography

APPLIN, J. and KUSAMA, Y. 2011 Yayoi Kusama. Edited by Frances Morris. Edited by Frances Morris. London: Tate Publishing(UK).

BACHELARD, G. and JOLAS, M. 1992 The poetics of space. Boston: Beacon Press.

BISHOP, C. 2005 Installation art: A critical history. LONDON: Tate Publishing.

HARRISON, C. and WOOD, P.J. (eds.) 2002 Art in theory, 1900-2000: An anthology of changing ideas. 2nd edn. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

Manns, E. and STEPHENSON, K. (eds.) 2016 Yayoi Kusama. United Kingdom: Victoria Miro Gallery.

Websites

EDITORS, A. 2015 7 influential installation artworks you should know. Available at: http://www.artspace.com/magazine/art_101/book_report/the-art-book-installation-1-53012 (Accessed: 28 October 2016).

FERRELL S.S. 2015 Claremont colleges scholarship @ Claremont pattern and disorder: Anxiety and the art of Yayoi Kusama. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1569&context=scripps_theses (Accessed: 28 October 2016).

JENTSCH, E. 2008 On the psychology of the uncanny (1906) 1. Available at: http://www.art3idea.psu.edu/locus/Jentsch_uncanny.pdf (Accessed: 28 October 2016).

KRASNOW, D. (1999) Yayoi Kusama. Available at: http://bombmagazine.org/article/2192/yayoi-kusama (Accessed: 4 November 2016).

RHINE, P. (2012) Whimsy or dark psychosis? Tate modern Yayoi Kusama retrospective – review round up. Available at: http://artradarjournal.com/2012/06/13/whimsy-or-dark-psychosis-tate-modern-yayoi-kusama-retrospective-review-round-up/ (Accessed: 28 October 2016).

TATE (1997) Performing for the camera. Available at: http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/performing-camera (Accessed: 30 October 2016).

WINNICOTT ch3 (2009) Available at: https://llk.media.mit.edu/courses/readings/Winnicott_ch3.pdf (Accessed: 28 October 2016).

TATESHOTS: Kusama’s obliteration room 2012 Available at: http://www.tate.org.uk/context-comment/video/tateshots-kusamas-obliteration-room (Accessed: 30 October 2016).

Journals

SULLIVAN, M.R. 2015 ‘Reflective acts and mirrored images: Yayoi Kusama’s Narcissus garden’, History of Photography, 39(4), pp. 405–423. doi: 10.1080/03087298.2015.1093775.

THOMAS, E. 2016 ‘“Meccano work”: Eduardo Paolozzi’s kits’, Sculpture Journal, 25(1), pp. 101–115. doi: 10.3828/sj.2016.25.7.